New research findings on Adventist martyrs

28. Jan. 2025 / Science & Research

It was 20 years ago in the summer of 2005 that one of the most interesting archives in Germany opened its doors to researchers: the ‘Arolsen Archives’ - the International Centre for Nazi Persecution. At that time it was still called the International Tracing Service (ITS). The surviving documents from the concentration camps and prisons of the Nazi era are stored here, as well as personal belongings of the prisoners. The collection, which contains information on around 17.5 million people, has been part of the UNESCO World Documentary Heritage since June 2013. In addition to the documents of the various victim groups of the Nazi regime, there are also directories on forced labour, displaced persons and migration after 1945.

Due to the protection regulations, until 2005 only relatives of the victims and state authorities were able to obtain information about the documents in Bad Arolsen. For me, it was a great moment in my research that in 2005 I was one of the first people for whom the doors of the ITS opened and to whom the head of the institution offered the opportunity to view original documents. At the time, I chose the book of arrivals and departures from Flossenbürg, the concentration camp in Bavaria where Dietrich Bonhoeffer was killed on 9 April 1945. My heart was literally pounding as I leafed through the pages of the book, which was kept with German bureaucracy, to find the entries for 9 April 1945. Unfortunately, Bonhoeffer is not listed there because he - along with other prominent personal prisoners of Adolf Hitler - only reached the site a few hours before his execution and was never listed as an inmate of the Flossenbürg concentration camp.

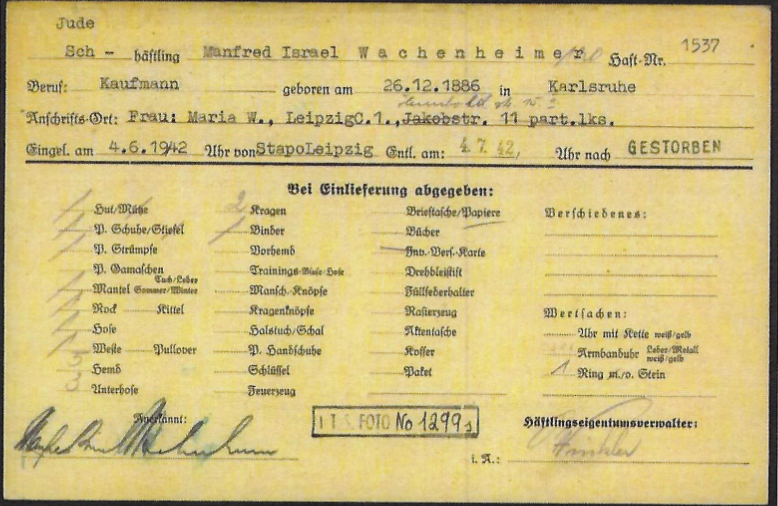

Instead, I came across another name - Manfred Wachenheimer. This Leipzig Adventist had been sent to Buchenwald concentration camp on 4 June 1942 for ‘unauthorised religious activity’ and was murdered just one month later, on 4 July 1942. In addition to the entry in the list of daily arrivals and departures from the Buchenwald camp, there are index cards with a detailed list of all the items of clothing and objects that he had brought with him on arrival - German thoroughness even when destroying them! What surprised me more in the daily entries, however, was a brief remark about his religious confession. Every prisoner had to declare his religious affiliation on admission. And so the usual abbreviations such as ‘Evangelical Lutheran’ or ‘Roman Catholic’ can be found, as well as ‘gg’ as a description for ‘believer in God’. During the Nazi era, anyone who had turned away from the recognised religious communities but was not without faith was considered a believer in God. Two or three other abbreviations for religious communities could be found. Some names also lacked the religious affiliation.

The abbreviation ‘adv.’ was used for Manfred Wachenheimer's religious confession. The explanation is clear to me. Manfred Wachenheimer was an Adventist. That didn't surprise me. What caught my attention, however, was the fact that an abbreviation was used for him at all. We normally only use abbreviations when we are talking about something that is not unique. So if an abbreviation for Adventists was used there, there must be other members of the church whose fate had probably remained hidden until then. And this is exactly what an initial search revealed. Names of Adventists that I had never read or heard of in this context. Unfortunately, there is no indication of which congregation they belonged to, and in many cases the date or place of birth is also not a clear indicator, because almost no congregational lists from the Nazi era exist.

In my experience, our collective consciousness as German Adventist churches is essentially limited to less than a handful of people who are known as martyrs. But that does not seem to be the end of the story by any means. Adventist martyrs unfortunately still have no lobby today, especially as their behaviour and courage at least indirectly called into question the attitude of those who remained silent out of fear or simple conformity; perhaps they just wanted to get away with it somehow.

The exceptions are a blot on the otherwise harmonious picture. Although almost no one alive today had reached the age of majority at the end of the war, the cloak of silence remains largely spread over the Adventist martyrs. They did not deserve that! On the contrary, we owe them thanks and recognition for their courage, for example in refusing the forced labour on the Sabbath and bearing all the consequences for it.

Even the Jewish members of the congregation could not fully hope for the help and support of their German sisters and brothers. Some were advised to stop attending church and not to take communion. Others reported that it did them good that people such as the head of the South German Association, Gustav Seng, or the preachers Otto Gmehling and Hermann Kobs stood by them without reservation and also visited them at home. The spectrum here was as diverse as it could be, but in the majority of cases - according to my perception based on interviews with survivors - fear was the underlying motive for many decisions, even when dealing with them.

Today, historians assume that after Jehovah's Witnesses and Catholic priests, Adventists were the third largest group of religious victims during the Nazi era, the majority of whom probably belonged to the ‘reform movement’. Much remains to be done to publicise and raise awareness of their fates. We owe it to them (Text and Photo: Dr Johannes Hartlapp).

Image Rights: Dr. Johannes Hartlapp