80 years ago – 1945 the zero hour?

16. Apr. 2025 / Science & Research

The end of the Second World War is perhaps the greatest turning point in German history of the 20th century. The signing of Germany's unconditional surrender in Reims and a little later on 8 May in Berlin-Karlshorst is known today as the Day of Liberation. At the time, however, many Germans experienced it very differently. Influenced by Nazi propaganda, some still believed in the final victory and refused to accept defeat. A world collapsed, dreams were extinguished, almost the entire country lay in ruins. Countless people had lost their homes, refugee treks trudged along the roads, forced labourers enjoyed their regained freedom and sometimes plundered their way through the battered country. They were all labelled DP (displaced persons). This actually applies to the entire German population: displaced – uprooted.

In retrospect, it is often noted that the confession of guilt by the Protestant regional churches, the Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt of 19 October 1945, was a ray of hope in dark times and the beginning of a process of coming to terms with the past. Today we know that this declaration only came about as a result of pressure from ecumenical representatives, who had made all aid deliveries (care packages) for the churches dependent on such a declaration. It simply took time to overcome the shock of the end of the war.

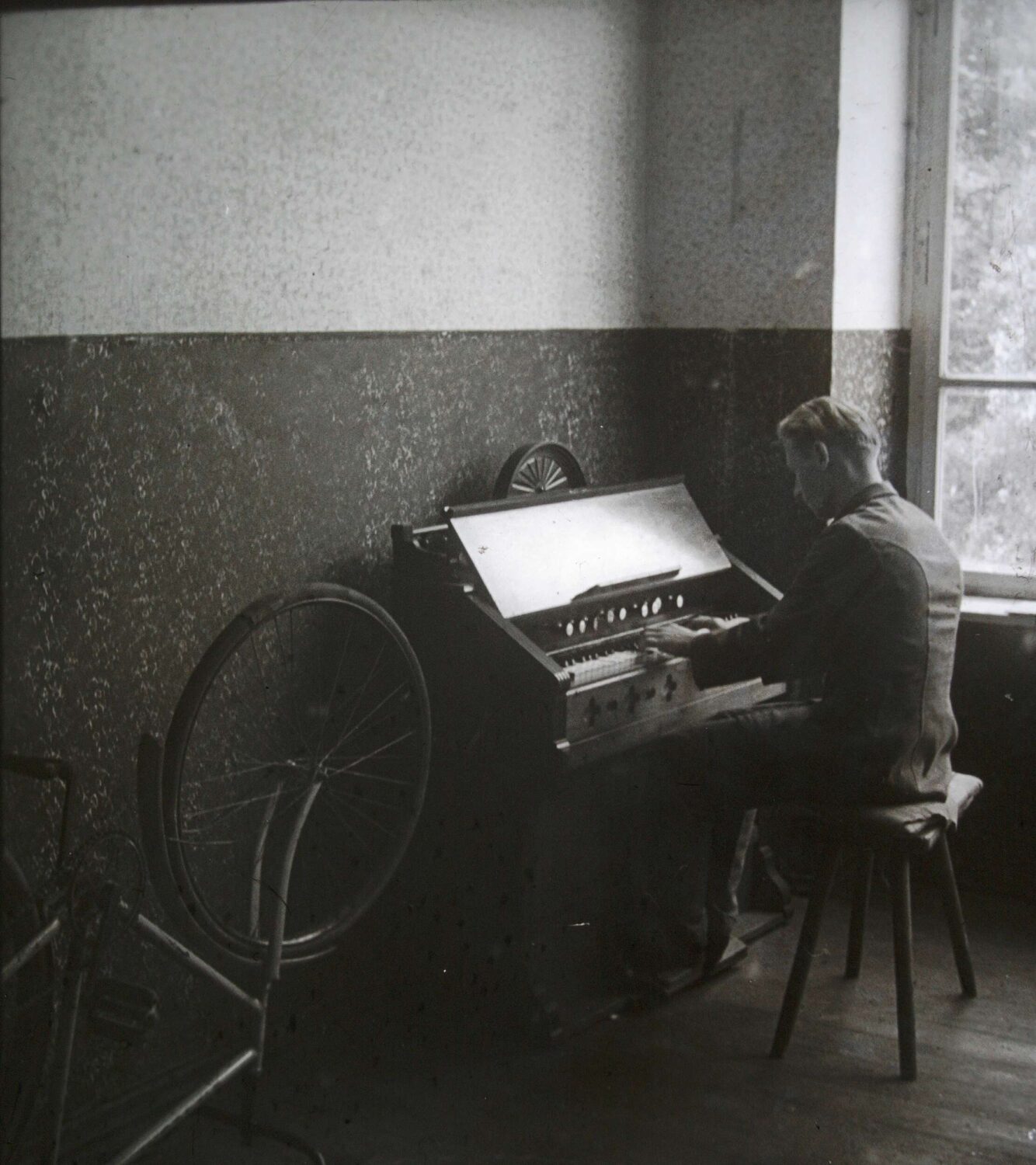

And in the Adventist Church? On Sabbath, 21 April 1945, the American military doctor MacAlpine met the head of the Middle Rhine Association, Albert Sachsenmeyer, while searching for Adventists in the heavily destroyed city of Frankfurt am Main. After the conversation, during which both discussed the situation of the church members and the situation of the community in Germany, Sachsenmeyer, following MacAlpine's request, wrote a report on the SDA community in Germany for the General Conference. At this time, fighting was still taking place in the north, east and south of Germany. Exactly two weeks later, on 5 May, Soviet combat troops entered Friedensau in the morning, three days before the surrender.

After the war had come to an end, it was time to take stock: The headquarters of the Central European Division in Berlin had been destroyed, and an alternative office had already been set up in Friedensau since 1942. All three organisations were faced with the ruins of their administrative headquarters, and the situation was no different in most associations. Thousands of Adventist soldiers had fallen, many church members - especially in the big cities - had lost their homes. The situation was no better for the church halls, many of which had already been confiscated during the war and, if not destroyed, were hardly usable for worship purposes at the moment. The biggest problem, however, was the large number of refugees who had been expelled from East and West Prussia, Silesia, the Sudetenland and other areas of Eastern Europe and were looking for a new home. They did not always find an open welcome in their communities. It was only decades later that some reported the rejection they faced in their time of need.

This was the biggest task in the first few months after the end of the war. Many congregations had to be reorganised, an administrative structure had to be established, relief supplies from the United States and Northern Europe had to be distributed and congregational life had to be secured due to the great shortage of preachers. As the publishing house in Hamburg had been destroyed and the British authorities were very reluctant to grant printing licences, the church newsletter, the ‘Adventbote’, could not be published. The situation was different in southern Germany: through the mediation of an American Adventist officer, a separate magazine, ‘Der Botschafter’, was published in Munich as early as the summer of 1945.

This was also urgently needed, as the time of crisis brought many people to the churches, some of them no doubt because of the coveted aid packages. People everywhere were looking for help and safety in difficult times. It was a time of evangelisations and baptisms. This was the main focus of the church leadership over the next five to seven years. The congregations grew, there was a lot of singing, a lot of time spent together. Almost nobody thought about coming to terms with the past. It didn't seem appropriate for the situation at the time.

Nevertheless, there were individual voices that felt a sense of responsibility for the past. Participants at the reopening of Friedensau on 5 July 1947 recalled that the old and new division leader Adolf Minck ‘expressed in his consecration prayer that we as German SDAs had become guilty’. Others did not come to this judgement, but adopted a metaphor that Albert Sachsenmeyer had already used in his report to the General Conference in April 1945: ‘It is only thanks to the grace of God and the fact that he did not refuse or withhold his help from the leading brothers that our fellowship in Germany still exists like a strong tree, albeit bent and strongly moved by the storm.’ Such a view made an understanding of the need to come to terms with the Nazi era superfluous for decades.

We owe the fact that – with some delay – a reappraisal of the events took place after all, which from today's point of view was partly unsuccessful, to the silence of German officials and the reports of American Adventist officers who held senior positions in the American military administration in Berlin. Their reports formed a picture that understandably had to remain one-sided. Due to the lack of postal connections and travel authorisations within Germany and abroad, misunderstandings arose that stood in the way of an orderly and necessary new beginning. There were also theological questions. In the past, Adventists had given virtually no thought to state ethics. They looked ahead to the Second Coming and the corresponding prophetic framework, which was given far more attention than the fundamental political upheavals worldwide since the end of the First World War and, above all, the dictatorship in Germany since 1933.

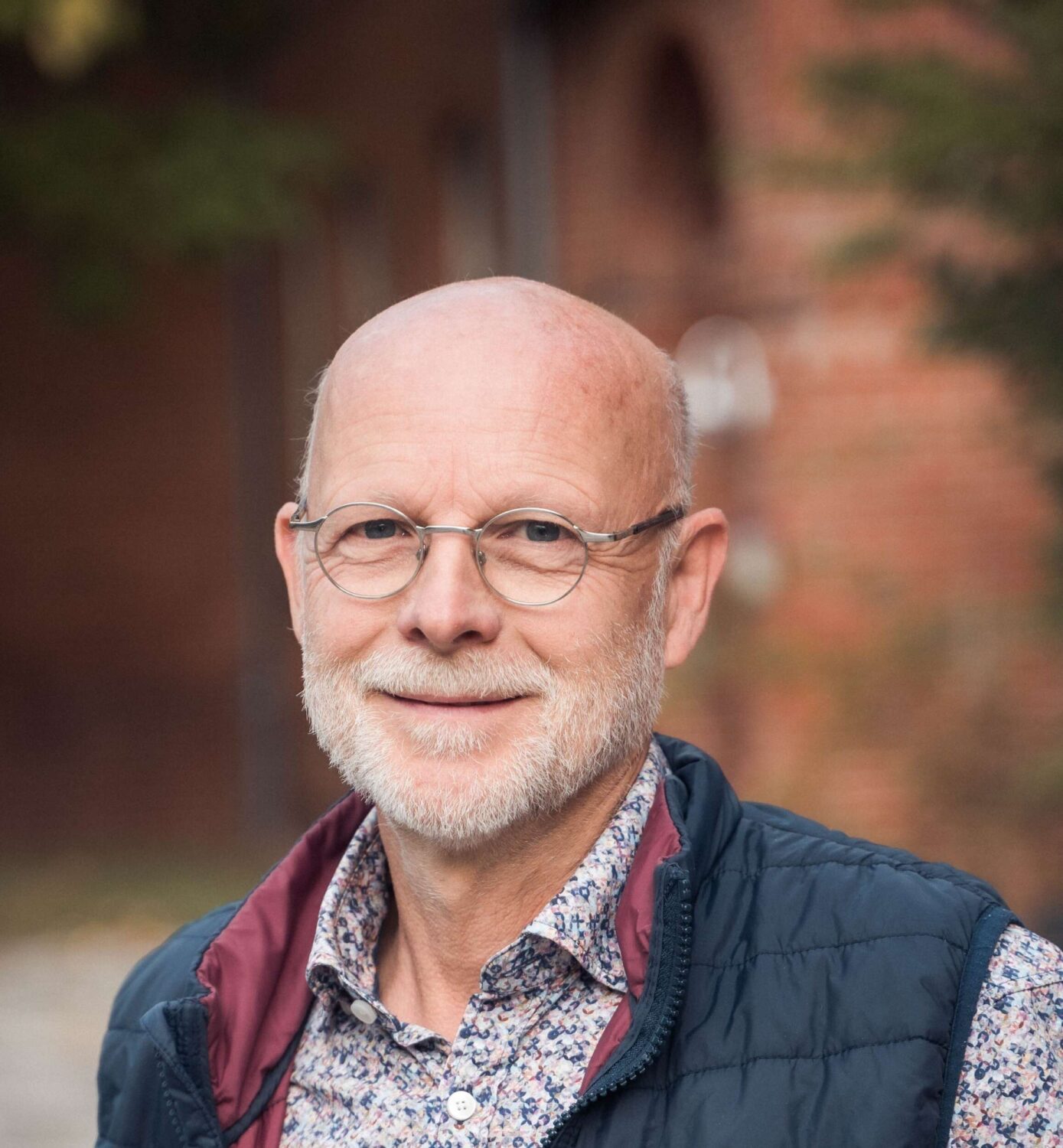

It was not until February 1947 that GC President James L. McElhany made direct contact with the head of the Central European Division, Adolf Minck. Two months later he sent a letter with a series of questions about the behaviour of German SDAs during the Nazi era. A direct consultation should have begun here, because the questions raised, for example with regard to Sabbath observance, were also burning under the nails of many church members in Germany. However, the answer only came months later. It failed to convince the General Conference leaders, especially as Germany had been under general suspicion since the resignation of Ludwig Richard Conradi in 1932. However, this suspicion undermined a real debate and a learning process about the behaviour of Adventists in authoritarian regimes. This was later to take bitter revenge in other countries around the world. It was not until 1952 that representatives of the Central European Division took part in the General Conferences, which were still taking place more frequently at that time. This resulted in a new appointment to the division leadership – a belated zero hour (Dr Johannes Hartlapp).

Quotes from: Johannes Hartlapp: Seventh-day Adventists under National Socialism. Göttingen: V & R unipress, 2008, 605 and 478.

Image Rights: Friedensau Adventist University | Michael Bistrovich

Image Rights: Archives | Johannes Hartlapp

Image Rights: Archives | Johannes Hartlapp

Image Rights: Archives | Johannes Hartlapp